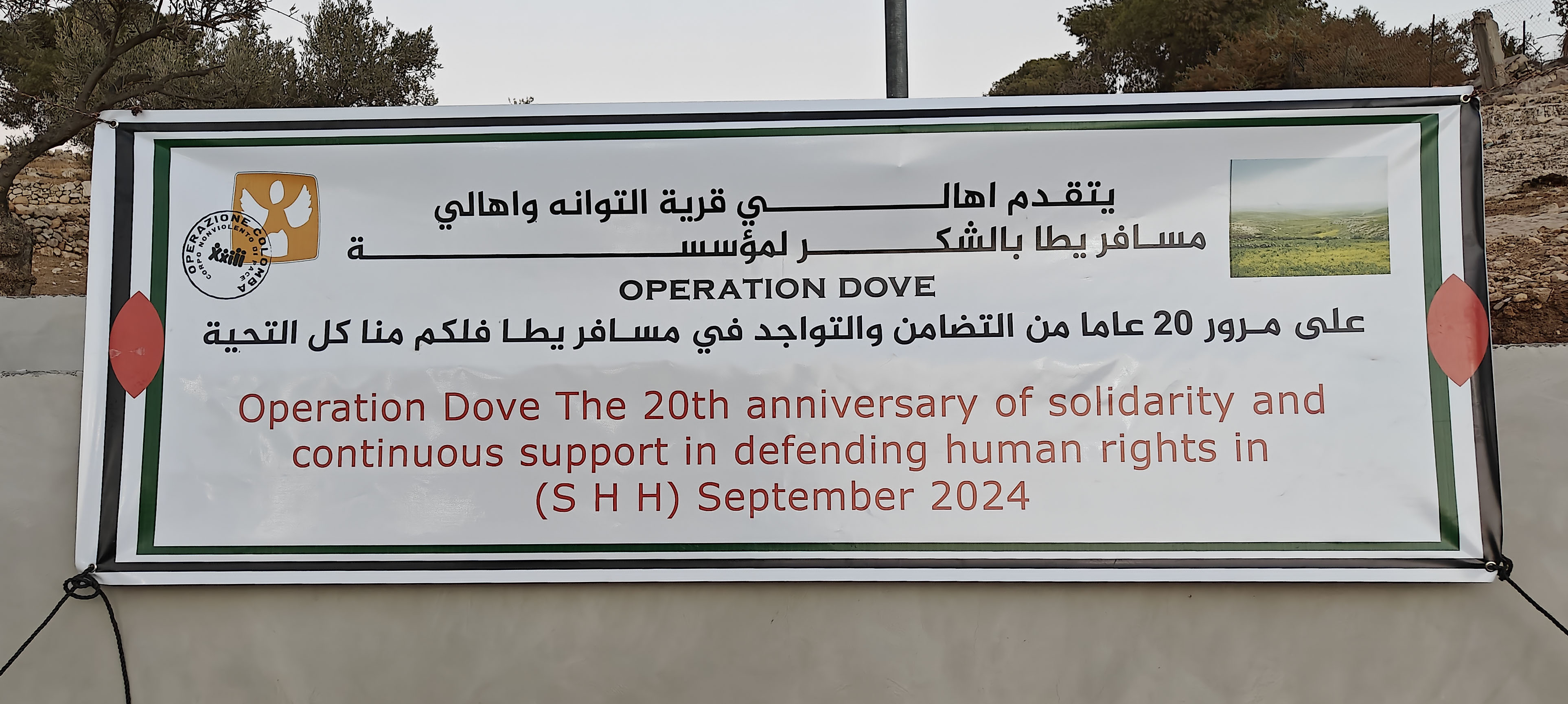

Wires with lighted bulbs swing suspended over the neat rows of chairs where all the guests are taking their seats. Some of them are very elegant, some in flip-flops, one man arrives on the back of a donkey, and another parks his tractor next to the cars. The atmosphere reminds that of a village festival, men greet each other, some faces are familiar to all, the ladies and younger boys and girls sit to one side, all well-dressed for the occasion. In front of everyone stands a banner celebrating the presence of Operazione Colomba in the area: 20 years of solidarity and continuous support in defending Human Rights in the South Hebron Hills.

There are five of us here - four adults and a little girl - representing dozens and dozens of volunteers who over these 20 years have accompanied and protected the Palestinian communities of Masafer Yatta from the violence of the Israeli occupation, from the prevarication of settlers and soldiers who unfortunately continue to besiege the area. I feel the incredible privilege of participating in this celebration, I am the newest arrived here, and nevertheless I enjoy the unconditional affection and gratitude that others before me have obtained through years of nonviolent accompaniment of shepherds under the scorching sun and nights spent awake on the rooftop of the house closest to the Havat Ma'on outpost. I am very lucky to be here, and I also feel a little out of place, as if I am usurping the place of those who would be more entitled than me to receive all this gratitude.

Some well-known activists, who bravely faced arrests and torture after October 7th, begin to speak. They thank us, even praise our actions. We are all clearly embarassed, and even those among us who are usually ready to joke are visibly moved. Then, it is the turn of activists in the area, the Mayor, the Human Rights defenders who fight to resist an increasingly aggressive occupation, and the young people who have grown up alongside the volunteers, and who now carry on nonviolent resistance with responsibility and pride, perpetuating their parents' choice and commitment. Each of them gives us a plaque with a written thank you note, and with each plaque our embarrassment grows. But it is at the end of the ceremony when we are all deeply moved: a young man, now a journalist and activist, takes the floor. He lives in Tuba, the village from which we have been accompanying children for the past 20 years so that they could reach the school in At-Tuwani safely, and could enjoy the Right to Education. The road would otherwise have been too dangerous to walk, due to continued violent attacks by settlers against Palestinian students.

“For 12 years I felt safe going to school because there were ajaneb (internationals)” he says. “The residents of Tuba, Um Zaytouna and Kharrouba, and even the goats who live in these valleys, all together, we say ‘Thank You Colombe’ ”.

We are all hopelessly overwhelmed with emotion.

Then, it is time for the women, who give all of us ceramic plates and cups painted with traditional Palestinian motifs, and at this point none of us knows what to say anymore. It's way too much to keep it all to ourselves, and so we try to share videos and photos with all the volunteers who have passed through these valleys, in a sort of return of gratitude received.

The evening continues with a real celebration: we all eat together, chat, say goodbye, and at the end even a giant cake with the logo of Operazione Colomba arrives.

Some say they didn't think we would stand by them after October 7th, after the settlers fired at us. Many people recount this episode as if something incredible and unexpected happened. I have the impression that this has brought us even closer to those who suffer this reality of violence every day, and that choosing to stay nonetheless has confirmed our credibility.

As the evening draws to an end, we thank everyone several times, say goodbye to those who are leaving. Late at night we find ourselves drinking coffee with the guys from the village, who fortunately dilute our emotion with teasing and a few jokes. In the end, it has been 20 years of blunders in Arabic, terrible gaffes, quirky volunteers and bitter irony, all this to avoid succumbing to a daily life of abuse.

The next day is Saturday, and we are awakened by a call: settlers are celebrating Shabbat by entering a family's home at 6 a.m. to ask the women who are baking bread to show their IDs. The brutal reality of the occupation brings us back down to Earth, after a dreamy night. At the same time, two settler shepherds graze their flocks on Palestinian land in the valley as if it was their own. How much patience this choice of nonviolent resistance requires.

We continue to accompany these communities, the promise to resist alongside them is renewed, hoping to stay for the next 20 years to spend time together without the need for passport or camera, just for the pleasure of drinking mint tea under the lit light bulbs of the celebration.

To paraphrase someone, after all, a laugh will even bury the occupation!

S.

OPERAZIONE COLOMBA

OPERAZIONE COLOMBA